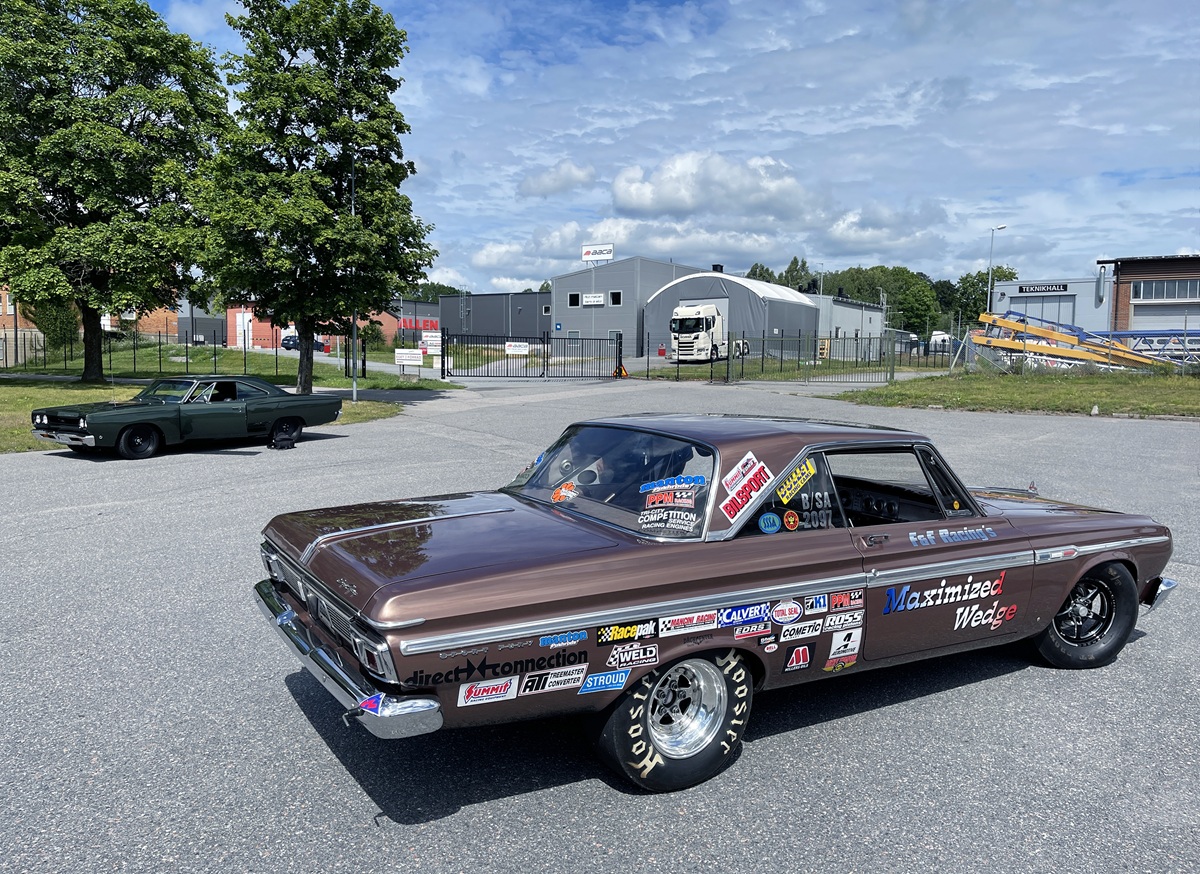

Purchased new in Sweden by a young woman named Stina Sjögren, this 1964 Plymouth Sport Fury has lived an extraordinary life. It was stolen years later by a criminal gang known as the “Rotebro Gang” and abandoned in a gravel pit. In 1999, Fredrik Frisberg acquired the car and converted it into a Stock-class racer under the strict and conservative rules governing the category.

We meet – myself, Fredrik Frisberg and his father, Christer – at the decommissioned F13 air force base in Norrköping. This was once home to one of Sweden’s most iconic aircraft, the Saab 37 Viggen. On October 28, 1981, during the infamous Soviet submarine incident near Karlskrona, Viggen fighters stood fully armed and fueled, ready to launch at then-Prime Minister Thorbjörn Fälldin’s command.

Around that same time, the Rotebro Gang – active from the mid-1970s to about 1985 – likely stole the elegant Sport Fury, wreaking havoc with it. Exactly when the theft occurred remains unknown.

What is certain is that Frisberg, at 24 years old, purchased the car in 1999. He remarks that he was already an “old man” in spirit, considering his choice of vehicle. At the time, most young car enthusiasts in Sweden favored muscle cars from 1968 onward, such as the Dodge Charger or Challenger, or the Dodge Dart for those on a tighter budget.

“When I bought it, the car had a 383-cubic-inch engine with 330 horsepower and a 727 automatic transmission. The car was equipped with 11-inch drum brakes. When it was recovered from the gravel pit, they used a forklift and straps, which left the rocker panels badly dented,” Frisberg explains.

Before Frisberg acquired the vehicle just before the turn of the millennium, it briefly served as a street racer. However, for most of its time, it sat idle in a garage. The last official inspection of the car in Sweden was in 1974.

“When I got the car 25 years ago, it had a 440-cubic-inch engine producing 620 horsepower. Almost everything else was original – transmission, brakes, rear axle – except for a sharper torque converter and a rear-end gear ratio of 4,56:1. It was a real sleeper. I drove it on the streets occasionally until I experienced throttle stick and damaged the front fender and bumper,” Frisberg recalls, sighing.

This wasn’t the only mishap early in his ownership.

“I once tried to show a non-car-enthusiast friend how to do a burnout, which resulted in snapping the driveshaft. It took the transmission with it, spraying automatic transmission fluid onto the headers. The car smoked like crazy.”

Before this incident, Frisberg had taken the Sport Fury to the drag strip at Tullinge, south of Stockholm. Despite weighing 1,870 kilograms (4,123 lbs), the car clocked an impressive 11,26 seconds over the quarter-mile, thanks to assistance from his father, Christer.

“Around year 2000, Dad bought a 1968 Chevrolet Corvette convertible with a 327-cubic-inch, 350-horsepower engine and a manual transmission. But after our success at Tullinge – and my throttle mishap – it felt natural to focus our efforts on the Sport Fury. He sold the Corvette to finance our Sport Fury-project.”

Frisberg has always admired the NHRA Stock Eliminator drag racing class. Together with his father, he decided to build the Sport Fury to comply with its regulations.

“The car is a Stock-class vehicle, even though the decals on the valve covers say ‘Super Stock.’ When the car was built in 1964, Super Stock was the designation. Those are original decals,” Frisberg clarifies.

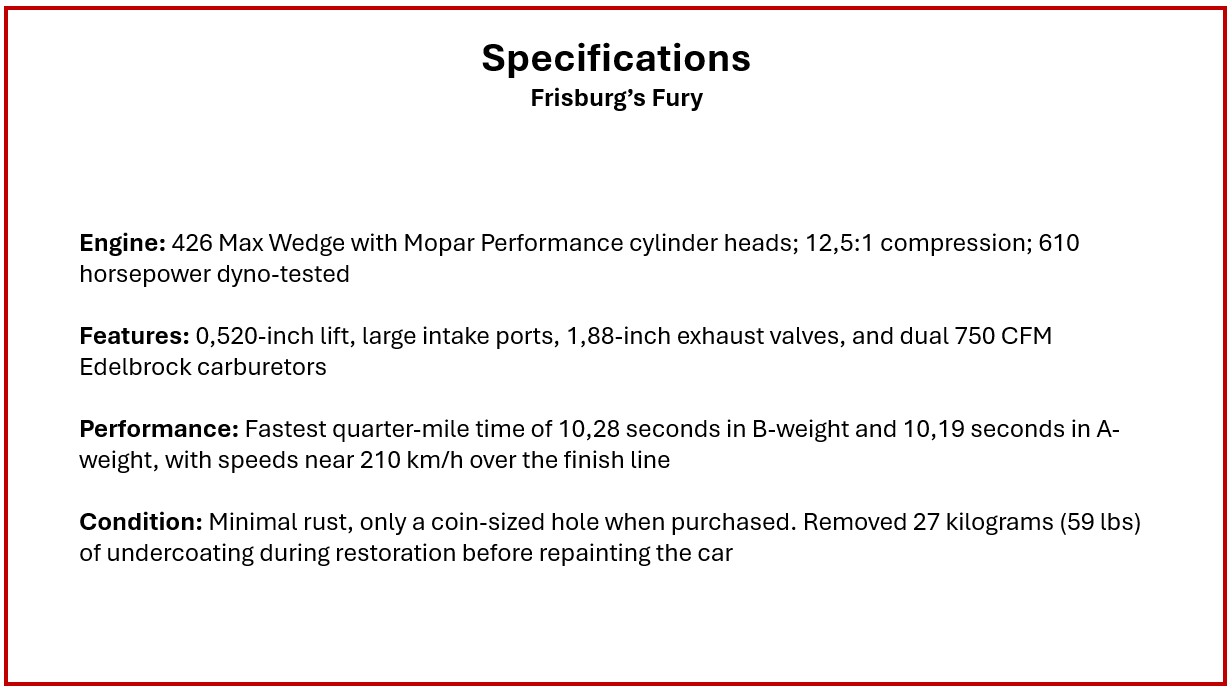

He adds that he finds the cross-ram intake manifold both cool and unusual, as is the choice of engine – a 426 Max Wedge V8.

Curious about the strict regulations governing the Stock class, I ask Frisberg to elaborate.

“In the class, you can choose from any factory engine offered for the car model that year. If the V8 came with a mechanical camshaft, that’s what you must use. Maximum nine-inch-wide slicks. No porting of cylinder heads or intake manifolds. Camshaft lift must match the original specs, but duration is free. Pistons, rings and connecting rods can be replaced, but they must meet minimum weight requirements.”

Frisberg explains that the NHRA provides a list of approved replacement parts if originals aren’t used. Brakes and seats can be swapped for safety reasons, which often reduces the car’s weight. However, any weight savings can be added back to the rear of the car for better traction.

For their Sport Fury, Frisberg calculates:

“Our V8 is rated at 403 horsepower for our class, reduced from the factory rating of 415 to ensure competitiveness. This makes it a natural B-class car. B has a factor of 8,5. You multiply the horsepower by the factor, add 170 lbs for the driver, and then convert to kilograms for Sweden.”

He walks me through the math:

“403 x 8.5 = 3,425. Add 170, and you get 3,595.5 lbs. Converting to kilograms gives us 1,632 kg. That’s our car’s minimum weight. You can move up or down a class, changing the weight and index. The index determines qualifying times; the further under the index you run, the better your position and prestige.”

Frisberg explains that in bracket racing, drivers estimate their car’s time and aim to get as close as possible without going under. If two cars in the same class race, it’s a “heads-up” race to the finish line.

“Our index in B/SA (Stock Automatic) is 11,25. If we ran a manual transmission, it would be B/S.”

Frisberg chuckles, noting how Stock racing can become an expensive hobby: “Good cylinder heads, intake manifolds, carburetors – they cost a fortune. People swap out transmission components for aluminum ones to reduce weight. Every detail is optimized for performance.”

Despite the high costs and intense competition, the Frisbergs – father and son – are fully committed to the sport.

0 Comments